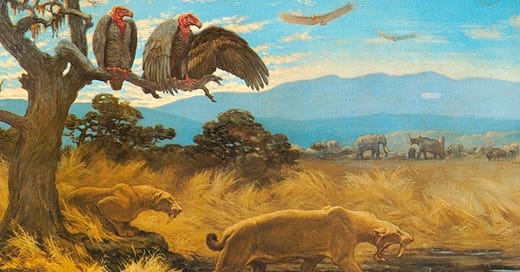

Smack dab in the middle of Los Angeles, off Wilshire Boulevard, lies the La Brea Tar Pits, described as the "richest paleontological site on Earth for terrestrial fossils of late Quaternary age." Natural asphalt bubbles up through the ground and creates deposits which are often covered with a thin layer of water or leaves. Animals wander in and are quickly trapped by the thick, sticky tar. Beneath the surface, animals, plants, and insects are permanently preserved as fossils, some from as long as 38,000 years ago.

This reminds me of a "sticky" situation in chess, "Zugzwang". You see, there was one last step an animal made at La Brea that was its last before doom, that doom being the first step into the tar. In chess there is an equally fatal tar pit: Zugzwang, which comes from the German words "Zug" (to move) and "Zwang" (compulsion), is when you are forced to move AND every move you could make makes you worse off. This is true in La Brea and true in zugzwang.

In a 9th Century analysis, Zairab Katai first describes this situation, involving four chess pieces - - black king with knight, white king with rook. At a certain juncture, black is doomed, every successive move is a worse one - - after the paw has entered the tar.

[After 1. Re3 Ng1, 2. Kf5 Kd4, 3. Kf4 comes zugswang, as black must abandon its attack on the white rook, allowing white to trap the black knight.]

Games like checkers and chess force each player to move on his turn. Mother nature has its own Zwang, its own compulsion: The mouse, even in the death grip of the boa constrictor, must breathe. After zugswang, it's over for mouse and for man.

LIFE CAN PRESENT ZUGZWANG MOMENTS - - ONLY SALVATION IS AVOIDING THEM!

Joseph Bertin states in his "The Noble Game of Chess" (1735), "To play well the latter end of a game, you must calculate who has the move, on which the game always depends." A movie with the same lesson is the 1983, techo-thriller "WarGames", starring Matthew Broderick. In the film, the world is at the brink of nuclear war accidentally triggered by computer. We are saved when the computer calculates its way to the conclusion: "the only winning move is not to play." That is, humans must avoid the zugswang of a triggered, nuclear escalation - - don’t the step into the tar!

One must be wary, in our personal and work lives, and avoid zugswangs - - that is, maneuver when you are free and fully-able to do so. Maneuver out of the way of life's tar pits, to shape the game in your favor. Awareness and early avoidance is the only escape from zugzwang.

Let's look at another perilous situation, another of mice and men, one where quick wit and action can save our skin. Ambush.

I watched a number of nature videos of snakes stalking mice. In one, a boa constrictor had its prey stranded on a branch. The snake continued its calculated, methodical motion toward the mouse. Realizing the peril - - perhaps sensing its personal zugswang - - the mouse leapt from the branch and plunged downward through the forest canopy. While this fall would be fatal to a human, the mouse survived. Zugswang avoided.

Ambush is common to humans as well: It is a tactic in warfare as old as war itself. Ambush, when executed well, conveys enormous advantage to the attacker, enabling even small, out-gunned forces to win an engagement. The ambusher leverages pre-planning, terrain, and surprise.

Soldiers are trained not only how to set ambushes but also how to escape them. Like the mouse choosing the canopy jump, humans must choose an immediate peril to avoid (eventual) zugswang.

In the most simple form of ambush, the ambusher selects a corner in a trail, a road, or a cityscape. He arrays his forces to stop the movement of his enemy and engages from both the front and side of the traveling column. Online, one can find hundreds of videos of this "L-shape" ambush in practice; it is found in nearly every war movie, from "The Last of the Mohicans" to "Sicario".

REACTING IMMEDIATELY - - EVEN AT GREAT COST - - SAVES ONE IN AMBUSH

The military doctrine "react to ambush" teaches the only way to survive: One must immediately return enemy fire, seek cover or conceal oneself with smoke, and assault through. That is, one has to immediately attack into the ambush - - this is the perilous mouse jump into the forest canopy. Attacking the attacker is the only way to survive - - one must choose their fate now - - face peril now, lest zugswang later.

Action movie fans might recall the over-the-top scene in the 1987 film "Predator", with Arnold Schwarzenegger, when they "react to ambush" by an ALIEN! [look for "Predator contact scene"] The team reacts immediately, by muscle memory.

For mouse and man, indecision is the killer. Facing ambush, either by snake or human, avoiding the zugswang is the goal - - dynamic, risky action is the only chance to avoid that fate.

This piece is another in a theme I am exploring: Very often one must make the choice to take a hard, painful action in the present to avoid a worse fate down the road. This is a key skill for both leaders and individuals. See also the earlier, “Healthy Prunes”. Stick with me as I dig more deeply into these types of trade-offs and the decision making processes behind them.