Sports are a crucible, forging participants into something new and better. This is true for both the individual and the team athlete. The lessons and habits we develop last a lifetime, a library of mental and muscle memories from which we can draw. As spectators we can also enjoy the drama and share, as announcer Jim McKay famously stated on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, “the thrill of victory, and the agony of defeat”.

There is much we can learn from studying sports. Sports gives us powerful metaphors for larger things in life: As a footballer struggles to move down the field so does a soldier fight to move past the enemy's line. We marshal forces on the soccer pitch and in our organizations.

I'm particularly interested in how innovation happens in competitive sports. Why and how does everything suddenly, dramatically change? Who does "disruption" and how does it happen? Seeing it can help change the ways we think about innovation and creativity, both as individuals in our own work and collectively in the work in our organizations.

Let's look at a couple, remarkable "leaps" in sports. First, in track and field, the high jump.

High jump traces its origins to Scotland in the 19th Century. It's been included in the modern Olympic Games since they began in 1896. For about a century, jumpers ran toward the bar diagonally and jumped over while scissoring their legs; this was the standard. Variants appeared over the next seventy years, such as the "Eastern Cut-off", the "Western Roll" and the "Straddle". These were all important evolutions, though incremental and gradual.

The world changed dramatically for high jumpers when Dick Fosbury debuted his innovative new style in the 1968 Olympics in Mexico, clinching the gold medal with a winning height of 2.24 meters. Fosbury ran at the bar in an aggressive "J"-shaped approach and went over the bar back-first, ultimately landing on his back. Here's the remarkable jump.

Fosbury the innovator, used his academic talent and knowledge of mechanics to pioneer this new technique. He reinvented the jump: No athlete jumps the "old" way anymore. His method, called the "Fosbury Flop", reigns supreme, even today.

Before we draw some lessons from Fosbury, I'm going to tell you another great innovation story, this time from swimming, the breaststroke. This example is near and dear to me, as I've always been a strong breaststroker and am now the proud father of two young men, both great breaststrokers.

A decade after Fosbury made history, a Hungarian coach named Jozsef Nagy developed a new way to do the stroke, called the "Hungarian Wave" or the "rollover". Nagy felt the current method, where swimmers swam below the surface like an alligator, was inefficient. Inspired by the work of Nobel physicist Richard Feynman, Nagy believed swimmers should undulate while they swim, likening it to the motion of cheetah on the run. Three swimmers coached by Nagy swam the 200 meter final in the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games, including József Szabó who powered to the gold medal and new world record at 2:13.34. After this, people no longer told Nagy he was crazy; his stroke become the standard.

What can these two stories teach us about innovation?

INNOVATION BEGINS WITH DISSATISFACTION AND STING OF FAILURE

Both Fosbury and Nagy were unhappy with the current method in their sport. They saw the technique as clunky, inelegant, and inefficient. Fosbury, in fact, struggled to qualify for high school meets using the standard jump at the time.

In your own work, in your own organization, are there processes where you get that same feeling? Is it you, or a colleague, who feels that way but is pushed aside and told "It's you. It's not the way we do things?"

I remember one day during my time as a Production Group Leader at Toyota when a Team Member in my group approached and described a problem. I'll never forget her closing the discussion with "That's not the Toyota Way". You see, she didn't need, herself, to know THE better WAY - - she possessed something valuable, a belief in the people in her organization, a belief that it was possible to find a better way.

INNOVATION REQUIRES A BELIEF IN A BETTER WAY

I cringe when I hear a "leader" say, "I don't want problems, I want solutions!" Great organizations, great leaders, listen to these truth tellers. Don't push them aside.

INNOVATION REQUIRES AN EXPANSIVE, OPEN MINDSET

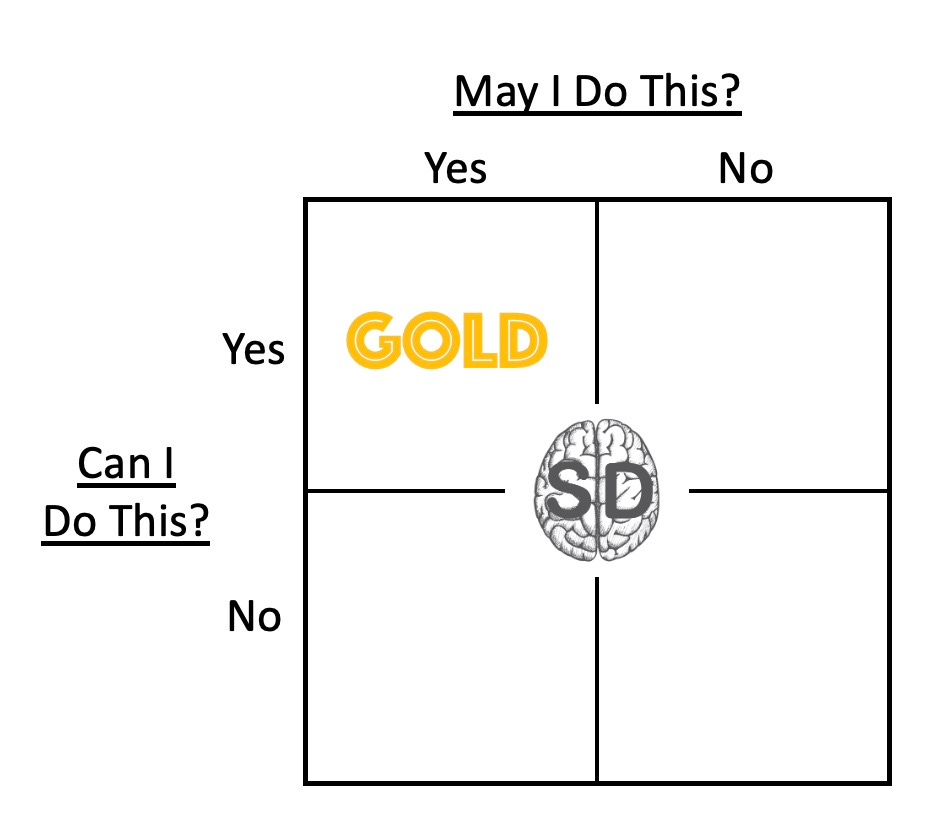

Let's take a quick look at the high jump. The Olympic rules for the event are quite simple. You must leap from one foot. You may use the runway approach any way you like. You may not touch the side supports or dislodge the supported crossbar. Oh, and there is a limit to the thickness of your shoe sole and heel. That's it.

I want you to visualize something. I want you to see that the set of things the Olympic rules says you MAY NOT do is very small compared to the set of things you COULD do. In fact, the set of possibilities is infinitely larger.

Now, I wouldn't be a true BCG person unless I stuck in a two-by-two matrix! Imagine, two axes, one is what is permissible by those rules we discussed above, a simple yes or no. On the second axis we'll ask ourselves, "Can I do that?", again a simple yes or no.

In your own work, or in your own organization, ask yourself a couple questions:

What is the set of rules? What are the laws, regulations, or social norms that limit what I can do? Are they pretty detailed, are they concrete?

What freedoms do I have outside of these limits? What are the most basic assumptions that I am making about how I should approach this endeavor? How is my own thinking constraining that set of beliefs?

How did Fosbury look away from the crossbar? Was it written anywhere in the rules that you had to face it? Is it human instinct to look at something - - an obstacle - - when we jump over it? When you approach that second step, that second question above, you must question your most basic beliefs about the things that you do and why you do them.

Fosbury challenged fundamental belief more than once. He not only looked away from the bar to clear it with his back but also ran away from the bar with his "J"-hook approach! Jumpers always tried to get close to the bar when they jumped: Fosbury had the insight that the leap was an arch - - to go higher, the base of the arch must be further from the bar - - this was a conceptual leap!

INNOVATION REQUIRES EXPERIMENTATION AND DOGGED PERSISTENCE

Both Fosbury and Nagy began to experiment with potential solutions. Both men looked outside their sport for inspiration. There were many trials and many errors along the way.

Detractors were many. Fosbury was frequently discouraged by others and told to continue jumping with the known method. One reporter said, disparagingly, that Fosbury looked like "a fish flopping in a boat" and another said his approach looked "lazy". People thought coach Nagy was crazy. Ultimately the success of the new, superior methods silenced the critics.

In your own work, or in your own organization, you must cultivate a mindset that fosters experimentation. It is important that you guard that mindset. It is important that invest both the time and resources needed to experiment with new approaches.

We at Toyota had processes and tools to support this: That is why my team member was confident in the "Toyota Way". Seek to build that competence in yourself and your organization. I will devote future posts to creative tools and processes.

INNOVATION HAS FLOPS AND WAVES

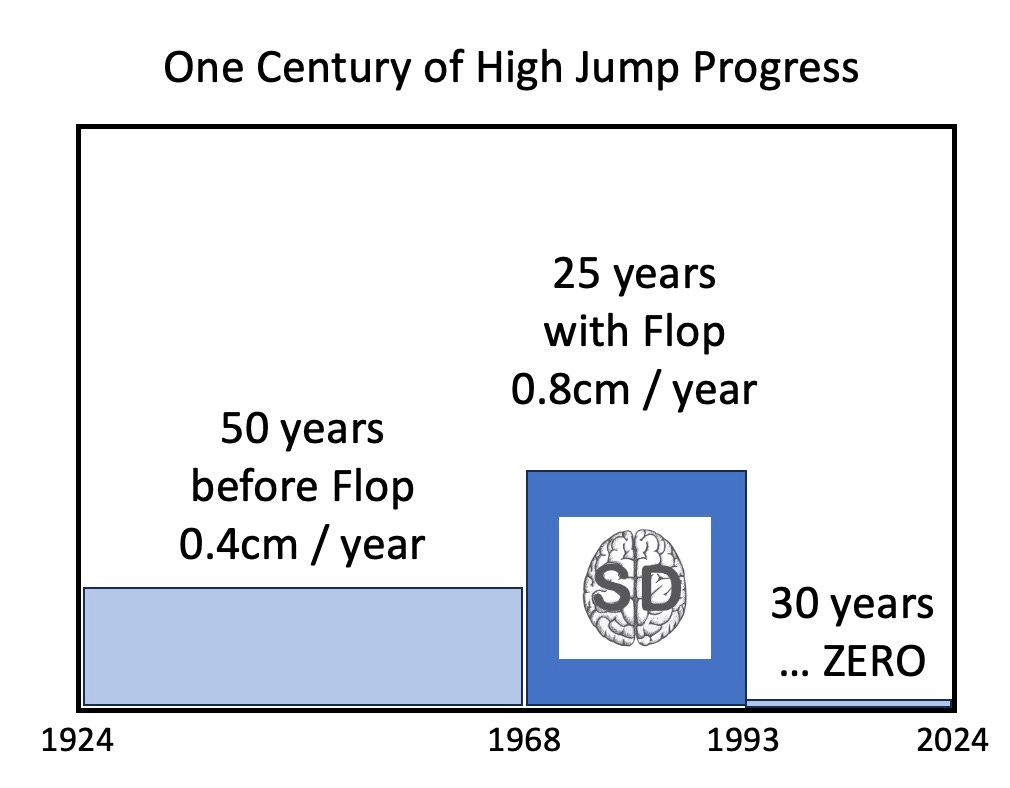

A final thought: Innovation, and creativity generally, comes in chunks and lumps. It is rarely constant or predictable. You see it in the high jump.

Let's look at the progression over a century, by tenths of a meter: 2.0 m in 1912 by George Horine, 2.11 m in 1941 by Lester Steers, and 2.22 m in 1960 by John Thomas. It took fifty years to go 20 centimeters higher!

Then, after Dick Fosbury, 2.3 m was cleared in 1973 by Dwight Stones, 2.4 m in 1985 by Rudolf Povarnitsyn. The next twenty centimeters in half as long!

The world record is held today by Javier Sotomayor, at 2.45 m, set in 1993. We've been stuck at that height for thirty years now. We could take a look at these three eras. (The record was 2.03 m in 1924.)

Innovation can have these patterns. There's no real way to know, but it's likely the "old" method was was dead before Fosbury came along - - perhaps progress would have been flatlined. Even with the advent of computer modeling in training, we seem to be stuck at 2.45 meters.

Does this pattern, this lull, signal that the high jump is again, ripe for an innovation? Do you know of other examples of dramatic innovation, in sports, in the arts? Give me your thoughts in the comments.

Of course, please use the buttons below to help support me and this work. Beyond that, I ask you to consider a bigger set of possibilities. Can you, like Dick Fosbury and Jozsef Nagy, find other different ways as well? I don't know … write the url on the company whiteboard, slip it on a note to an artist friend who's in a dry spell. For me, for yourself, try one new thing, another, new approach. Thanks!